Discrete and Algorithmic Mathematics Red de Matemática Discreta y Algorítmica

Recent Trends XII: The mathematical art of experiment design

18 Dec 2025From Biology to Economics, experiments play a crucial role across the sciences. In many cases one has a lot of freedom in how to design an experiment. How do you design it well? How do you make sure it is fair and efficient? For answers to these questions, we can turn to Mathematics and in particular, a corner called Combinatorics, where such questions have been formalised and studied for centuries. Two key concepts arise - randomness and combinatorial designs. Despite huge progress in the mathematical understanding of these notions, one key challenge remains, namely how to marry these two ideas and generate random designs. This is a notoriously hard problem, but recent breakthrough results open up entirely new vistas and the future of the mathematical art of experimental design looks very bright.

Randomness: Making experiments fair.

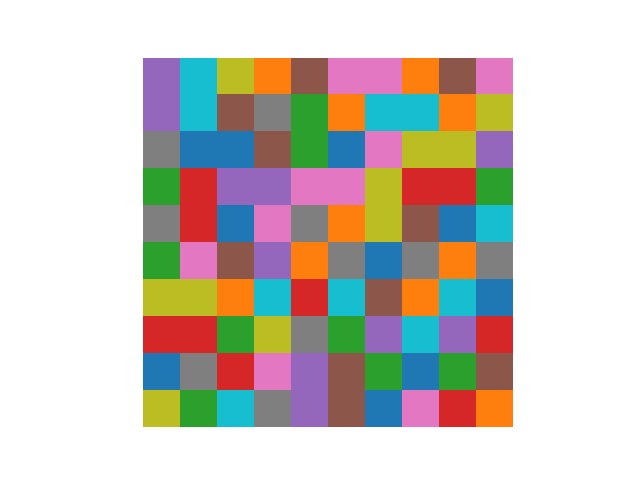

Suppose you want to compare the effect of $n$ different fertilisers on a crop. You have $n$ batches of each fertiliser and an $n \times n$ field split into unit lots. A first idea is to assign fertilisers row by row (Figure 1). This arrangement is neat, but not fair: any directional influence, say a pest arriving from the South, could disadvantage the fertiliser placed in the last row.

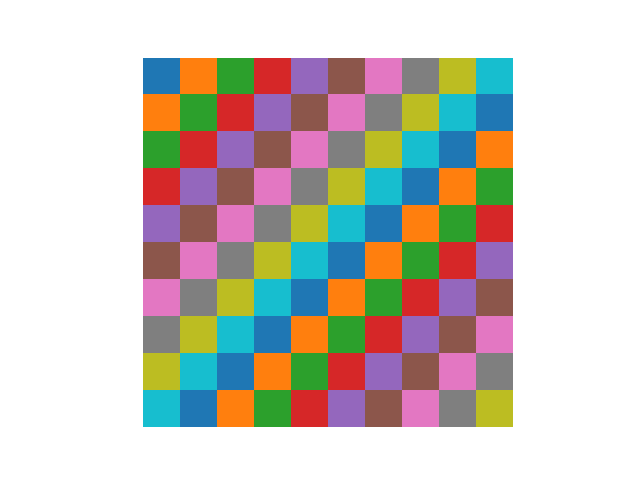

To avoid such bias, we need an arrangement with no hidden structure. A simple and powerful solution is to distribute fertilisers randomly: for each lot, roll an $n$-sided die to choose a fertiliser. A random layout, such as the one in Figure 2, avoids unintended patterns.

The idea of using randomness to construct objects with desirable properties was popularized by Paul Erdős in the mid-20th century and became known as the Probabilistic Method. Many combinatorial structures that are hard to build deterministically, arise naturally through random choices. This perspective launched the study of random discrete structures.

Randomness helps protect an experiment from unwanted influences, but difficulties arise when there are additional factors we do want to measure. Suppose each row of the field corresponds to a different height and each column to a different water level. We still want a fair arrangement, but also need data for every fertiliser at every height/water combination. A purely random layout fails here: many rows and columns will miss some fertilisers.

One way to fix this is to increase the field size. If the field has $m \times m$ lots and we place $n$ fertilisers randomly, then each row and column will likely contain every fertiliser, provided that $m$ is larger than $n \log n$. This is a classical instance of the Coupon Collector Problem. In such a layout, each fertiliser would appear on average $m/n\geq \log{n}$ times per row or column. Although this yields good coverage, it is inefficient: the extra $\log n$ factor forces us to use many more lots, fertiliser batches, and a larger field overall.

Combinatorial Designs: Making experiments efficient.

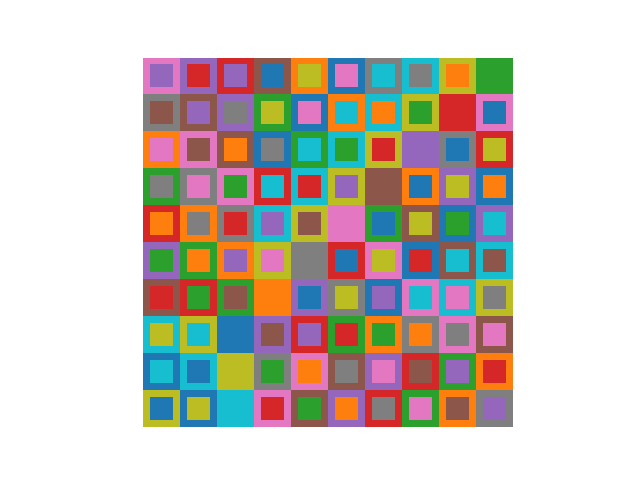

Can we use an $n\times n$ field and exactly $n$ copies of each fertiliser while ensuring that every row and every column contains each fertiliser once? Since randomness cannot guarantee this, we might revisit ordered layouts such as Figure 2. At least that arrangement tests each fertiliser at every water level. In fact, the diagonal pattern in Figure 3 gives exactly what we want.

Mathematically, such an arrangement is an $n$-Latin Square (LS): an $n\times n$ array with entries from $[n]$ where each symbol appears exactly once in each row and column. Introduced by Euler, LSs are fundamental in Design Theory and familiar from Sudoku, which is simply a $9\times 9$ LS with extra $3\times 3$ constraints. Euler also studied Mutually Orthogonal Latin Squares (MOLS), pairs of LSs whose superposition never repeats symbol pairs (Figure 4). In the experimental analogy, using two LSs corresponds to testing fertilisers and pesticides simultaneously so that every combination is observed.

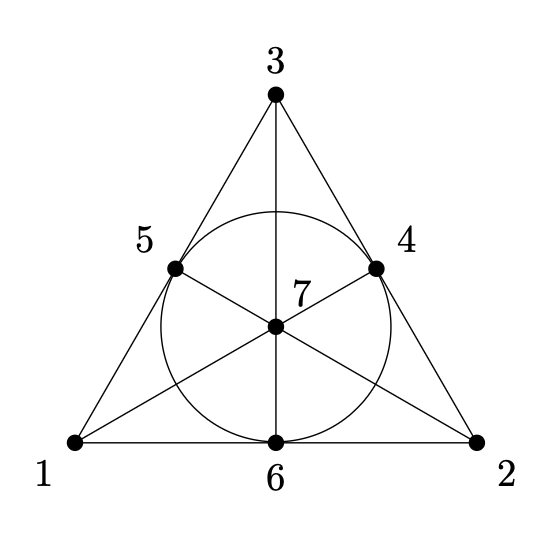

Combinatorial Designs, of which LSs and MOLSs are examples, are highly symmetric collections of subsets of a finite set. Their use in experimental design was pioneered by Fisher in the 1920s–30s, but they also appear in the construction of efficient error-correcting codes. A classical example is the Fano Plane, a Steiner Triple System (STS) on $7$ points in which each pair lies in exactly one $3$-set (Figure 5). By turning each point into a binary word indicating membership in these $3$-sets, and completing the collection with the zero word and complements, one obtains the $(7,4)$-Hamming code, an optimal code that corrects one error or detects two.

$$

\begin{align*}

S_1&= \{1,3,5\}\qquad v_1 = 1010100\\

S_2&= \{2,3,4\}\qquad v_2 = 0111000\\

S_3&= \{1,2,6\}\qquad v_3 = 1100001\\

S_4&= \{1,4,7\}\qquad v_4 = 1001001\\

S_5&= \{2,5,7\}\qquad v_5 = 0100101\\

S_6&= \{3,6,7\}\qquad v_6 = 0010011\\

S_7&= \{4,5,6\}\qquad v_7 = 0001110

\end{align*}

$$

$$

\begin{align*}

S_1&= \{1,3,5\}\qquad v_1 = 1010100\\

S_2&= \{2,3,4\}\qquad v_2 = 0111000\\

S_3&= \{1,2,6\}\qquad v_3 = 1100001\\

S_4&= \{1,4,7\}\qquad v_4 = 1001001\\

S_5&= \{2,5,7\}\qquad v_5 = 0100101\\

S_6&= \{3,6,7\}\qquad v_6 = 0010011\\

S_7&= \{4,5,6\}\qquad v_7 = 0001110

\end{align*}

$$

Another famous design is Kirkman’s schoolgirl problem (1850), which asks for arranging $15$ girls into triples over $7$ days so that no pair repeats. This is another STS, now partitioned into $7$ disjoint sets of triples. Like LSs, it is an optimal way to ensure every pair interacts exactly once, and it illustrates how nontrivial constructing designs can be.

%A natural generalisation of STSs is the $(n,k,t)$-Steiner system (SS), where we choose $k$-subsets on an $n$-element set so that every $t$-subset appears in exactly one block. A basic necessary condition for such a system is the divisibility condition: since there are $\binom{n}{t}$ $t$-subsets in total and each block contributes $\binom{k}{t}$ of them, $\binom{k}{t}$ must divide $\binom{n}{t}$. Much of 20th-century Design Theory was devoted to determining when such systems exist and how to construct them. Some designs follow simple rules, such as the diagonal LS where the entry in row $i$, column $j$ is $F_{k+1}$ with $k = i+j \bmod n$, while others, like Kirkman’s problem, require far subtler ideas from geometry or algebra.

Random designs: The best of both worlds.

We have seen that randomness gives fair experiments, while designs give efficient ones, yet neither method is flawless. Randomness can create redundancy when several factors must be tested, and designs may impose symmetries that introduce bias. For example, in Figure 3, if a diagonal of the field receives extra light, the fertilisers assigned to the (light-)blue diagonal gain an unfair advantage.

A natural idea is therefore to construct designs randomly. Yates already suggested in 1933 that one should ideally “choose a square at random from all the possible squares of given size’’. Figure 6 shows a random LS of size $10$, which indeed appears balanced. However, generating a uniformly random LS is extremely difficult. Even for size $10$ there are $7{,}580{,}721{,}483{,}160{,}132{,}811{,}489{,}280$ distinct LSs (two squares are considered the same if one is obtained from the other by permuting rows and columns), and this number grows superexponentially, so direct sampling is impossible.

A major advance came in the 1990s when Jacobson and Matthews introduced an Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method for sampling LSs [2]. MCMC algorithms define local moves on a space of objects and then perform a random walk; after enough steps one expects to reach an object close to uniformly random. Analysing how long this takes is the study of mixing times. Because LSs have strict symmetry conditions, finding appropriate moves is difficult, and the key insight of Jacobson and Matthews was to use a “not so local’’ operation that still allows an MCMC walk. Their method seems to work well and is provably correct in the limit, but we still do not know whether it runs efficiently (in polynomial time).

Absorption: A new way to construct designs.

In 2014, Peter Keevash announced a result that transformed the study of combinatorial designs. He showed that, whenever the divisibility conditions hold, one can construct designs using the absorption method [3]. To understand the idea, consider trying to build an $n$-LS using a random process. As in our earlier random distributions, we repeatedly choose a random row, a random column, and a random symbol, but now we forbid any choice that violates the Latin square rules. This approach, known as the semi-random method or R"odl Nibble, introduced in 1985 [6], fills almost all cells, but eventually it gets stuck because no legal moves remain.

Absorption fixes this. Before the random process begins, we reserve certain absorbing structures: small configurations of rows, columns, and symbols with enough flexibility to complete many different partial squares. We then run the random process while avoiding these structures. When we get stuck, only a small portion of the LS remains unfilled, and the flexibility of the absorbing structures allows us to “absorb’’ the remaining cells and complete the square. The core difficulty is designing absorbing structures powerful enough to finish the job. Keevash achieved this using algebraic constructions; soon after, Glock, Kühn, Lo and Osthus [1] developed a purely combinatorial version called iterative absorption.

These breakthroughs provided the first genuinely random-influenced constructions of designs, objects that, while not uniformly random, retain many of the desirable symmetry-breaking features of randomness. The primary motivation, however, was to prove existence results. Constructing designs had long been difficult, and classical algebraic or geometric methods applied only in special cases. Although Wilson proved in the 1970s that $(n,k,2)$-SSs exist whenever divisibility conditions permit [7], general $(n,k,t)$-SSs remained out of reach, and Steiner had conjectured since 1853 that they should always exist for large enough $n$ under the same conditions. Keevash’s absorption method resolved this conjecture, giving constructions for all feasible parameters and, remarkably, the first examples of any $(n,k,t)$-SS with $t\ge 6$.

These ideas opened completely new directions. Not only do they construct many designs with given parameters, yielding the best known lower bounds on their total number, but they also allow designs with additional properties. For example, Kwan, Sah, Sawhney and Simkin used iterative absorption to construct high girth STSs [5], settling a long-standing conjecture of Erdős from 1973.

Towards understanding Random Designs.

Unfortunately, the absorption-based constructions of designs do not produce objects that are anywhere near uniformly random. The absorbing structures are delicate and introduce significant bias, overwhelming the randomness coming from the semi-random stage. Although these methods yield many designs, it is unclear whether they produce more than a negligible fraction of all possible designs. Generating designs that are genuinely random, or even close to random, remains unresolved.

Nevertheless, Kwan made a striking observation: if certain properties hold with very high probability in the semi-random process, then one can often deduce that uniformly random designs exhibit those properties as well. Building on Keevash’s framework, he derived upper and lower bounds on the number of ways a partial design can be completed, allowing him to compare the distribution on partial designs induced by the random process with that induced by the uniform distribution. Through this analysis, he proved new results about random designs. Most notably, he showed that a uniformly random STS contains perfect matchings [4], that is, a collection of disjoint $3$-sets covering all vertices.

Even with these remarkable advances, unimaginable before Keevash’s breakthrough, the study of random combinatorial designs is still in its early days. Many deep and appealing problems remain open, especially the challenge of actually generating random designs and thereby gaining access to ideal, unbiased experimental constructions.

References

- S. Glock, D. Kühn, A. Lo and D. Osthus. The existence of designs via iterative absorption: hypergraph $F$-designs for arbitrary $F$. Memoirs of the American Mathematical Society 284, monograph 1406, 2023.

- M. T. Jacobson and P. Matthews. Generating uniformly distributed random Latin squares. Journal of Combinatorial Designs, 4(6):405-437, 1996.

- P. Keevash. The existence of designs. arXiv:1401.3665, 2014.

- M. Kwan. Almost all Steiner triple systems have perfect matchings. Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, 121(6):1468-1495, 2020.

- M. Kwan, A. Sah, M. Sawhney and M. Simkin. High-girth Steiner triple systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2201.04554, 2022.

- V. Rödl. On a packing and covering problem. European Journal of Combinatorics, 6(1):69-78, 1985.

- R. M. Wilson. An existence theory for pairwise balanced designs III. Proof of the existence conjectures. J. Combin. Theory Ser. A, 18:71-79, 1975.

The authors of this post, Patrick Morris and Guillem Perarnau are researchers in the GAPCOMB group at the UPC.